- The main protagonist: Salmo salar - the Atlantic Salmon

- The Life Cycle of the Atlantic Salmon

- The Atlantic Salmon's Great Migration

- How do Atlantic salmon find their way home?

- Why is it important to protect Atlantic salmon and their migration patterns?

- The Threats

- 1. Dams

- Identifying the Barriers

- 2. Forests & Temperatures

- Reforesting the Riverbanks

- 3. Overfishing & Salmon Farms

- Monitoring Sea Lice Outbreaks

- Fast Facts about Atlantic Salmon

Salmon are one of the most recognisable and iconic fish species in the world. Their epic life journey takes them from their birthplace high up in the rivers all the way to the ocean and back to spawn and eventually die.

In the process, they support a multitude of other wildlife and ecosystems making them an all important keystone species.

Unfortunately, this wonderful cycle faces many threats and wild populations are declining rapidly.

Which is why in this article, we want to take a look at the Atlantic Salmon. More specifically the Scottish population, to better understand the threats they face and what we are doing to rewild their rivers to help this iconic fish thrive once more.

The main protagonist: Salmo salar - the Atlantic Salmon

Salmo salar is one of the 9 main species of Salmon that occur in two genera. The Oncorhynchus genus in the Pacific and the Salmo genus in the Atlantic.

As the name suggests, it is the only species of salmon that lives in the Atlantic Ocean. It is also the one that lives the longest, up to about 13 years, and the largest, growing to about 1.2 to 1.5 meters in length - or about the size of the average a woman from Guatemala!

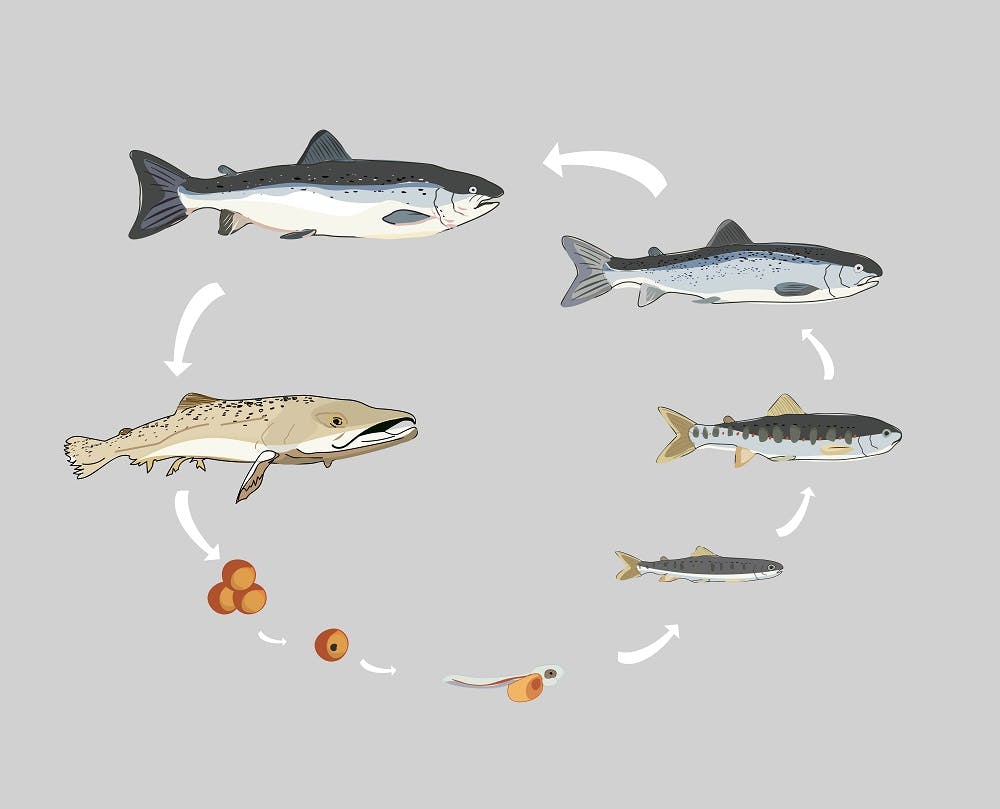

The Life Cycle of the Atlantic Salmon

The lure and intrigue that makes the Atlantic salmon so fascinating is its life cycle. It transforms from a minute, vulnerable fish to a seafaring species capable of undergoing perilous journeys thousands of miles to spawn back at the same place it hatched from itself. These are the 6 stages of the Atlantic salmon’s remarkable life cycle.

1. Eggs

Salmon start their lives in early winter as small fertilised eggs hidden by the females in the gravel of the river, generally a few feet under the surface. Depending on water temperature, eggs will usually hatch in early spring.

2. Alevins

The young, small fish (just 10mm long) called ‘alevins’ hatch with a bright orange yolk sac attached to them. They stay in the gravel for a few weeks as they absorb the sac and the nutrition it provides. In late spring, the juvenile fish is ready to embark on the next stage of its life's journey in the river.

3. Fry

Now measuring about 3cm in length, the ‘fry’ start hunting small insects and aquatic plants until they grow to become ‘Parr’. At this tiny size, fry are prey to other fish, birds, and insects. It is at this stage that they are most vulnerable.

4. Parr

As Parr, the fish will have visible markings on their sides to distinguish them. The young fish is not yet ready to venture out to sea though and will live in the river for another 2 to 3 years. The length of time spent in the river will depend on water temperature and food availability.

5. Smolts

When they reach about 12cm in length, they become what is known as ‘smolts’ where they take on a physiological transformation to adapt and survive at sea. Smolts will continue to grow and become more silver and gradually begin to leave the rivers for the sea in late spring until early summer.

6. Adults or Post-Smolts

By this point they are generally considered to be adults or ‘post-smolts’ when they have commenced one of nature's greatest migrations at sea.

The Atlantic Salmon's Great Migration

While not much is known about the migration pathways of these young adults, we do know they generally unite and move in schools when going to deep sea feeding areas.

For the Scottish salmon population, most fish will feed in the Norwegian Sea and Southwest of Greenland. The ones that go to Norway (named ‘Grilse’) tend to return after about 1 year while those that head to Greenland (known as ‘multi-sea-winter salmon') will stay at sea for 3 to 4 years and therefore grow larger feeding in a marine environment.

In the case of Scotland, ‘spring salmon’ have been recorded returning to Scottish waters between January and June. However, they can return at any time of the year meaning they're a constant part of a functioning ecosystem and the reason why they are considered to be so important for Scottish biodiversity.

How do Atlantic salmon find their way home?

After their life at sea, Atlantic salmon perform an extraordinary navigational feat by returning back to their native river to spawn a new generation to follow in their steps. They do this using their 'olfactory memory' by marking scents in their memory along their journey out to sea as young adults.

This incredible return journey to their birthplace can take the salmon over a year to complete posing many challenges and testing their perseverance and strength to the limits. The fish face an assortment of predators from dolphins, seals, and birds. Once they have reached the coast many will stop feeding, maybe to never feed again, while their kidney and other vital organs adjust to freshwater once more. Their sole focus becomes preserving their energy for the rest of the journey.

The long and arduous journey of the Atlantic salmon ends when they reach their spawning grounds in the Scottish Highlands, where heroically after spawning around 90-95% will die in a behaviour referred to as ‘semelparity’.

Sadly, for many Atlantic salmon this natural life cycle has stopped playing out. Before we discuss why and what can be done, here is why the Atlantic salmon is so important to the ecosystem.

Take action now

Do you want to have a direct impact on climate change? Sir David Attenborough said the best thing we can do is to rewild the planet. So we run reforestation and rewilding programs across the globe to restore wild ecosystems and capture carbon.

Get involvedWhy is it important to protect Atlantic salmon and their migration patterns?

A Keystone Species

Through their unique ability to live both in fresh and salt water and by travelling such distances, salmon act as a convoy of nutrients connecting marine and riparian ecosystems.

In the ocean they are an important middle link in the food-chain. They prey on small fish, such as herring, and are hunted by a variety of larger animals such as orcas, dolphins, tuna, sharks and seals.

In the rivers they are hunted by birds and mammals, such as the iconic relationship between the pacific salmon and the bears that hunt them. This of course, also used to happen in Scotland before humans pushed bears to extinction 1500 years ago.

Because salmon move up the river and die, they deposit marine nutrients in the soil around spawning streams which can have higher levels of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus than those of commercial grade fertiliser.

Healthy populations of Atlantic salmon improve the quality of life through Scottish rivers and which is why they are known as an 'indicator species'.

The Threats

Despite being one of nature’s best navigators, undertaking such an epic journey comes with many natural and man-made threats and obstacles.

1. Dams

Returning salmon face a bombardment of dangers not only from lurking predators but also rushing waterfalls and crucially, artificial obstacles like dams.

A lot of Scotland's rivers are dammed for hydroelectric power and that means that a lot of the historical spawning sites are no longer accessible to salmon.

In addition, it seems that the issue can run both ways which is the case in the Kyle of Sutherland, a river estuary that separates Sutherland from Ross-shire in the Scottish Highlands.

Salmon that manage to make it above this hydroelectric dam get stuck there basically, they cant migrate back to sea, they get re-routed to another catchment that is practically landlocked which means the surviving adults that spawn above the dam and any juveniles that are born aren't ever able to make it back to sea once they get above this dam.

Hannah Kirkland, Conservation Biologist, Mossy Earth

Identifying the Barriers

Through a partnership with the Kyle of Sutherland Fisheries Trust, we are supporting efforts to tag salmon with acoustic tags to track their behaviour and movements.

This data will be invaluable in providing us with a clear picture of where the salmon are facing difficulties and how we can help create better connectivity in the river.

This project forms part of our mission at Mossy Earth to make Scottish rivers wilder. We run a rewilding membership where our members and partners such as inlumi, provide the funding to set up a range of rewilding and reforestation projects across Scotland and Europe.

2. Forests & Temperatures

Another significant threat comes from deforestation and climate change.

In the face of climate change Scotland's rivers are warming which can be extremely detrimental to Salmon. It places them under a great deal of stress and at certain temperatures it can be lethal to Salmon.

The areas where Salmon spawn are supposed to be surrounded by trees that thrive on the moist soil and nutrient abundance. These forests help shade the water and keep it cool while also injecting additional nutrients in the stream and attracting all sorts of insects that young fry and parr can feed on.

Unfortunately many of Scotland's river banks have been barren for decades which has accelerated the decline of local salmon populations.

Reforesting the Riverbanks

To help fight this we have focused a lot of our reforestation efforts on river banks and hope to expand this to cover as many miles of river as possible.

By planting trees here we are not only helping to sequester carbon and create important terrestrial habitat but we can also improve the health of Scotland's rivers to safeguard the wildlife that depends on it.

We are planting a mix of native tree species including the iconic aspen which has disappeared from large parts of Scotland. You can read more about this project here.

3. Overfishing & Salmon Farms

Salmon also face many direct human threats such as overfishing and Salmon farms.

Captive salmon populations can escape and mix with the wild populations which leads to genetic erosion as many of the captive fish are genetically modified or at least not very genetically diverse.

Another issue is that they breed salmon closely together which leads to outbreaks of sea lice and disease that then spread to wild populations.

Monitoring Sea Lice Outbreaks

To help fight this we have started a project in Ireland. Together with our partners Arctic Stone, we are supporting the monitoring of sea lice in various rivers which is a crucial first step in assessing the extent of this crisis.

We hope to increase the size of this network in both Ireland and Scotland and eventually put this data to action to try and improve the situation.

River and marine ecosystems are often forgotten and suffer from a lot of environmental degradation. That is something we would like to change which is why we have set up these three projects. This is also why we are working on bringing back the lost kelp forests of Europe. You can learn all about that project in this video.

Fast Facts about Atlantic Salmon

- They are what's known as an 'anadromous' species, meaning they ascend up rivers from the sea to breed.

- Despite high mortality rates after spawning, some Atlantic salmon make it back to sea to feed and return again. This isn't the case for pacific salmon.

- A female salmon that has completed her migration 3 times will have swum more than 18,000 miles, survived many predators, and laid around 20,000 eggs!

- Many Atlantic salmon will die within metres of the exact spot they themselves hatched from.