The momentum behind tree planting initiatives is deservedly gaining speed, but we still aren't harnessing some of nature's most powerful tools. We should also be looking below the surface at blue carbon solutions. These ecosystems possess immense potential to capture carbon, enhance biodiversity and more.

The Climate Crisis

Seven years ago, the infamous Paris Agreement was signed. It was this international treaty that saw world leaders agree to limit their countries greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions on a pursuit to prevent global temperatures from rising. Legally binding targets were set to prevent temperatures from rising 2°C above pre-industrial levels with the ultimate goal of limiting the rise to under 1.5°C.

Unfortunately, fossil fuels have continued to be burnt (e.g. coal, oil, and gas), releasing copious amounts of carbon dioxide (CO2), and other potent gases such as methane and nitrous oxides into the atmosphere. An increase in GHG emissions is directly associated with rising temperatures, and the negative impacts associated with this phenomenon are worsening. Impacts are beginning to be documented more frequently, which includes an increase of storms, heat waves, floods, and droughts which all have associated indirect impacts e.g., wildfires leading to the loss of life and homes.

Nature brings the solutions

COP26 highlighted that we now have two fundamental solutions to mitigate climate change.

- Emission Reductions

The first is to reduce the output of GHG emissions, and this has proven to be trivial. It’s generally easier to limit emissions in higher-income countries who have the revenue to develop and install renewable and ‘green’ technologies. Whilst in developing countries, it’s the heavier reliance on the likes of coal for cheap electricity and the lack of economic resources to develop greener sources that continues to encourage fossil fuel use. - Carbon Sequestration

The other option we have is to increase carbon sequestration, the removal of carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere. CO2 is naturally removed from the atmosphere by the biosphere (plant world), and in the past 600 years, the land and ocean have taken up a near-constant proportion (globally ~56% per year) of CO2 emissions from human activities. The CO2 sequestered in vegetated marine and coastal ecosystems, specifically mangrove forests, seagrass beds, kelp forests and salt marshes, has been termed “blue carbon” and have proven to have higher sequestration abilities than terrestrial “green carbon.” For example, seagrass ecosystems can store 35 times more carbon than rainforests.

Here at Mossy Earth, we are currently focusing on two blue carbon ecosystems: seagrass meadows and kelp forests. Both these ecosystems provide boundless benefits to both marine life as well as humans, in addition to their unique capacity to sequester CO2. They are key to the survival of our oceans, which is why we are acting now, to help aid in the restoration of both habitats through a variety of partnerships and projects.

See the end of this article to find out exactly how we're trying to scale up restoration efforts in Europe. But first, let's dive more into the benefits of these blue carbon ecosystems.

Take action now

Do you want to have a direct impact on climate change? Sir David Attenborough said the best thing we can do is to rewild the planet. So we run reforestation and rewilding programs across the globe to restore wild ecosystems and capture carbon.

Get involvedThe Meadows of the Sea

Seagrasses are the marine environments only flowering plants. Like other grasses they have leaves and roots, which form rich underwater meadows. Seagrass meadows are found along many of the world’s coastlines in shallow water, from the tropics all the way to the arctic circle, except Antarctica. Although only occupying 0.1% of the ocean floor, seagrasses represent one of the largest global carbon sinks.

How seagrass sequesters carbon

To capture the carbon the aboveground seagrass foliage slows the water flow, causing the particles in the water column to settle and become trapped within the foliage. The particles from the water column are then absorbed into the sediments. Once carbon accumulates in the seagrass-vegetated sediment it can be preserved for thousands of years. This is partly due to the seagrass roots and canopy preventing sediment resuspension and to anoxic sediment conditions that reduce decomposition by the microbiota. It’s been predicted that they sequester around 20% of the carbon buried in ocean sediment annually.

Why seagrass is declining

However, seagrasses are under global threat, and it has been estimated that 29% of the known extent has disappeared since seagrass areas were initially recorded in 1879, making them amongst the most threatened habitats on earth. These rapid declines are mostly due to increased disease, water quality, and physical disturbance relating to boating activities and coastal development. The loss not only reduces the habitat functioning of the seagrass, but also, once removed, the sequestration potential of these habitats is lost, and the carbon accumulated over time can also be remineralised and released back into the atmosphere.

The Forests of the Sea

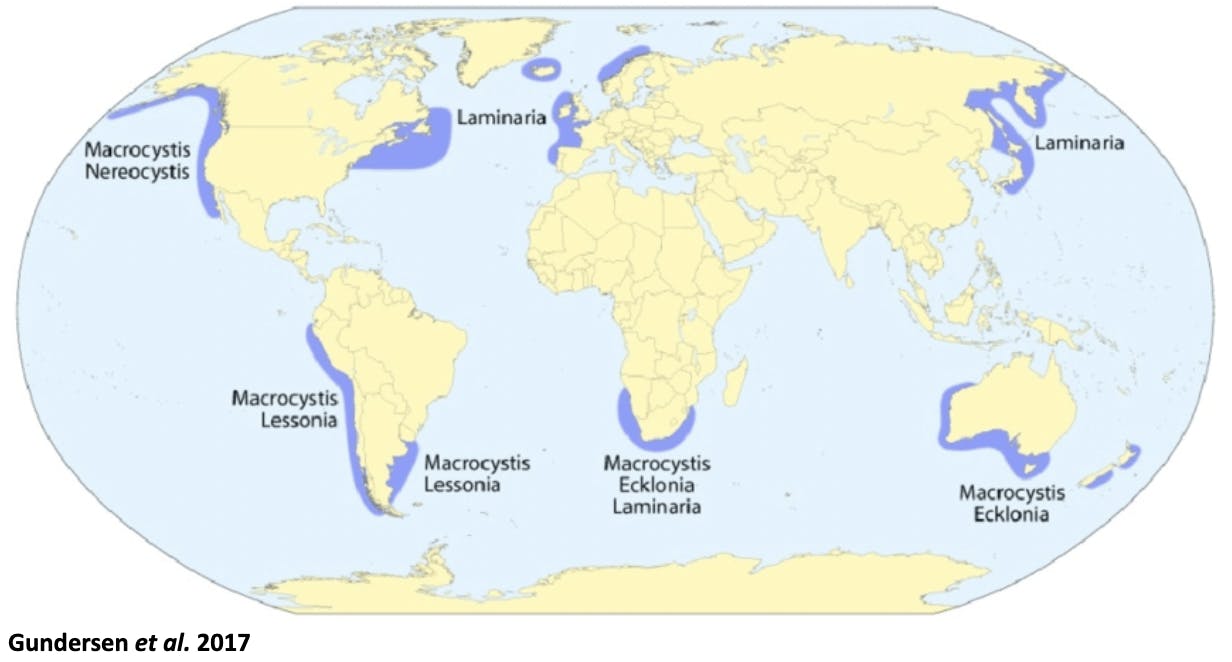

Kelp belongs to the order of Laminariales and is a brown macroalgae, otherwise known as a seaweed. They cling to the rocky seabed with their holdfasts (a root-like system), and form long and slender fronds of up to 30m that grow quickly towards the ocean’s surface. Light glistens through the water column, where they feed from the sun's energy (photosynthesis) to grow and form dense kelp forests. Through this process, carbon dioxide is removed from the atmosphere and converted and stored into various parts of the organism (the stipe, the fronds, the bladders, and the holdfast etc). Kelp forests occupy 25% of the world’s coastlines, where they prefer cold, nutrient-rich waters, so they are mainly associated with temperate and polar waters. Here are more fascinating facts about kelp.

- Kelp forests have some of the highest rates of primary production of any natural ecosystem, however in the past 50 years, global kelp abundances have declined by ~2% per year.

- Kelp forests, alike seagrass meadows harbour a great amount of biodiversity, which relies on thousands of finely balanced species interactions. If one or more of the species are lost, the entire system could be at risk of collapse. This has been devastatingly demonstrated in the kelp forests on the West Coast of America, where Sea Star Wasting Disease has caused a mass die back of sea stars.

- Purple sea urchins, who have a ravenous appetite for kelp, are the sea star's main prey. Without the sea stars to predate on the urchins their numbers are growing unchecked, devouring kelp forests at an unstoppable rate leaving behind ‘urchin barrens’.

- Unfortunately, urchins aren’t the only threat to kelp forests, human activities such as overfishing, pollution and climate change (i.e. rising water temperatures and harsher storms) are also a cause for worry.

Both ecosystems support a vast amount of biodiversity, by supplying habitats for thousands of species where they seek food and shelter. They also protect the coastline from erosion by stabilising sediments and reducing the impact of waves. But let us not forget, the other major attribute these ecosystems are capable of, and this is their capacity to absorb and store carbon.

Our efforts to scale up kelp restoration

We are in awe of these majestical, and invaluable ecosystems and notice their immense importance in tackling climate change and supporting biodiversity. To aid in their recovery, we have been busy establishing current and future restoration projects.

Trialing Seedling Techniques

Since forming a partnership with SeaForester in 2020, an initiative that aims to restore and reverse the decrease in seaweed forests around the world, we've launched several projects.

The first was based in Cascais, Portugal, and aimed to test a seedling technique using spore bags that are attached to rock surfaces. The mesh bags carried reproductive structures that would release spores and settle onto the rock to form new patches of kelp. Unfortunately this technique was not successful. We believe this was due to the amount of turf algae, which despite removing it from the rock surface beforehand, it outcompeted the kelp for space on the rocks.

As disappointing as this was, we felt it served as a valuable finding in our research and led us to develop a new approach with greater potential of scaling up restoration.

The Green Gravel technique

More recently, with SeaForester and the instituto politécnico de leiria (IPL) we built a kelp nursery in Peniche, Portugal to adopt a novel technique called ‘green gravel’. This technique enables the transplantation of kelp juveniles into the ocean without the need for diving. Although diving is a lot of fun, it can be incredibly time consuming and expensive. The green gravel technique involves growing kelp on small pieces of gravel in the lab in optimum conditions, which increases the production of Kelp by 10 times! After 3 months, when the kelp is an established juvenile, the gravel is dropped from a boat and left to sink to the ocean floor where the individuals then grow, reproduce, and establish a population in that area.

As the kelp is attached to its own gravel, the idea is it won't be affected by turf algae competing for rock surface. Then the goal is for the kelp to spread from the gravel to the reef and start seedling the forest. We were extremely pleased to see the results of the first trials as they proved to be a success! So we're building five modules, each capable of growing 12,000 kelp plants every 3 months! We run through the whole green gravel process and show you around the lab in the project video below.

All this is made possible because of our members, and the funding from our business partners and supporters, including the World Surf League. We also have some exciting plans in the making to start some seagrass restoration work up in Scotland, so please stay tuned as updates will follow this article in the coming months!

Sources & further reading

- “Ecosystem Services In the Coastal Zone of the Nordic Countries” - Gundersen, H., Chen, Wenting., Bryan, T, L., Moy, F, E 2017.