- Habitat fragmentation

- How much habitat fragmentation has happened?

- Goals for Biodiversity

- Where is habitat fragmentation happening and what are its effects?

- What are Wildlife Corridors?

- The purposes of Wildlife Corridors

- The benefits of Wildlife Corridors in action

- Criticisms of Wildlife Corridors

- Successful Wildlife Corridor stories

- Failures

- Do Wildlife Corridors actually work?

- How to support Wildlife Corridors

Our thirst for development over the past few centuries has left little of the planet’s land surface untouched by humankind. The effects of our presence have fragmented natural landscapes and impacted the habitats of the wildlife that live and depend on it. Wildlife Corridors offer the chance for wildlife and nature to reconnect and reestablish. Where Wildlife Corridors work, the benefits are vitally important and where they are suffering, the consequences are grave.

Habitat fragmentation

Habitat fragmentation is specific to the breaking up of a natural environment or patches of vegetation into smaller, disconnected sections. It is generally a consequence of agricultural activities, road building or housing developments. A complex web of flora and fauna requires an abundance of resources: food, air, water, sunlight, and the right habitat to survive. Devastation, degradation, and fragmentation of ecosystems caused by human development means that natural habitats, resources, and species are becoming highly limited and cut off from each other. For a species to sustain themselves successful breeding must take place. But when there is nowhere to live, resources are scarce and mates are difficult to find, they need to adapt or face the possibility of dying out.

How much habitat fragmentation has happened?

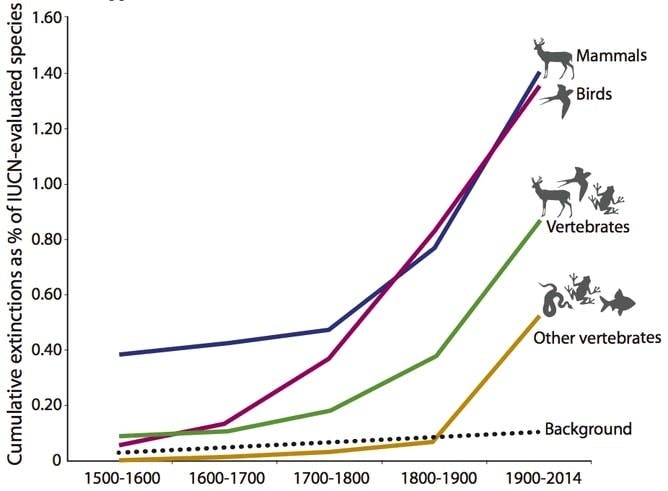

The 2019 Global Assessment on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services reports that human impact is responsible for the current 1 million plant and animal species facing extinction (ISPBES, 2019). The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) is the most comprehensive report ever completed, building on the landmark Millennium Ecosystem Assessment of 2005, and introducing innovative ways of evaluating evidence. It found:

- The average abundance of native species in most major land-based habitats has fallen by at least 20%, mostly since 1900.

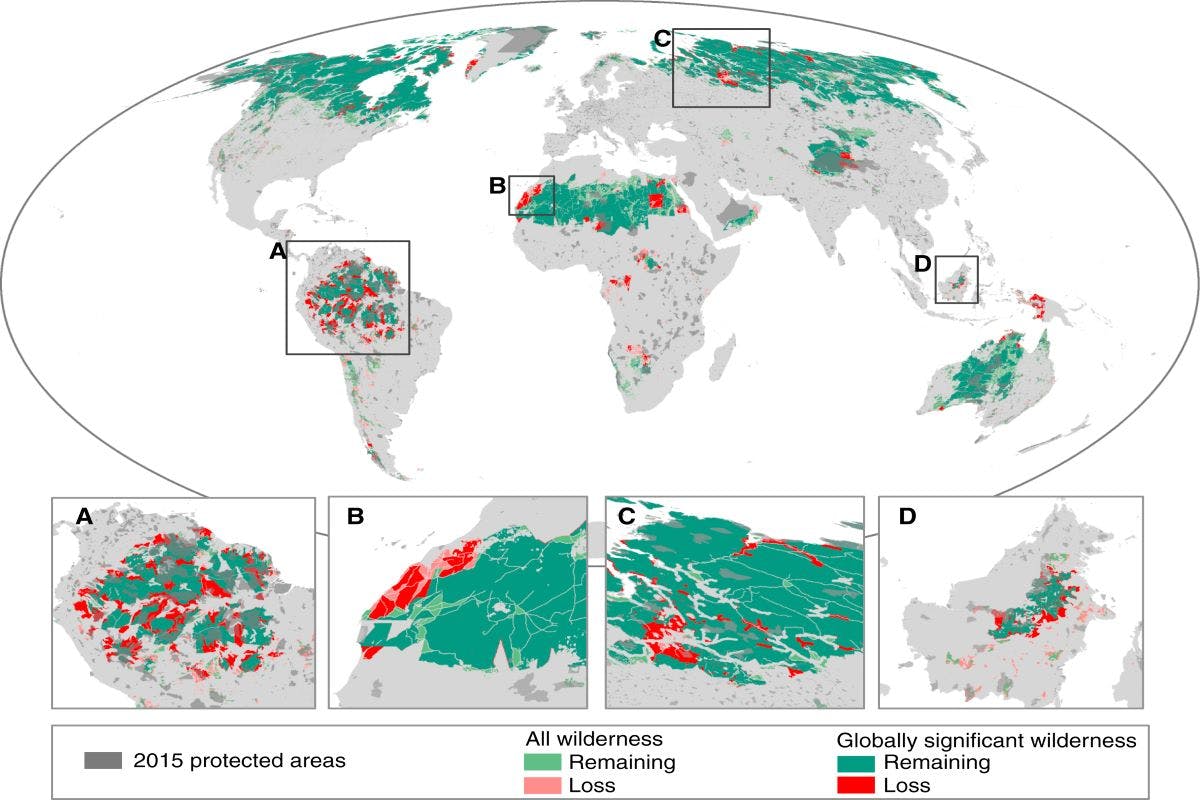

- Three-quarters of the land-based environment have been significantly altered by human actions.

- 68%: global forest area today compared with the estimated pre-industrial level.

- Urban areas have more than doubled since 1992.

The Report assesses changes over the past five decades and is compiled by 145 expert authors from 50 countries, including Prof. Settele who states:

“Ecosystems, species, wild populations, local varieties and breeds of domesticated plants and animals are shrinking, deteriorating, or vanishing. This loss is a direct result of human activity and constitutes a direct threat to human well-being in all regions of the world.”

Goals for Biodiversity

The UN also released the fifth Global Biodiversity Outlook report in 2020, recalling Aichi targets set back in 2010 with respect to biodiversity goals. Its results are bleak: Governments failed to meet a single target to slow the loss of the natural world. It is the second consecutive decade that targets were missed. Whilst some goals were partially fulfilled with 44% of vital biodiverse areas now under protection (an increase from 29% in 2000); others, such as a leading target to halve the loss of natural habitats, were not met.

Where is habitat fragmentation happening and what are its effects?

The effects of habitat fragmentation are varied throughout the globe, yet they impact a wide range of natural habitats and species. Here are some examples:

Natural Parks are abundant in Italy with over 20 National Parks and about 140 regional parks covering 10% of the land surface. However, Cinque Terre, Abruzzo, Lazio and Molise National Parks are where the natural habitat fragmentation, due to transportation infrastructures, is much higher.

In the Brazilian Amazon, research has shown that fragmentation within Amazonia has led to changes in forest dynamics, structure, composition, and microclimate, making remaining spaces highly vulnerable to droughts and fires; not to mention intensive hunting within fragmentation further threatening wildlife populations.

Intertidal wetlands and mangrove forest habitats are also at risk. In Southeast Asia, a global hotspot of mangrove loss, research found conversion to aquaculture and rice plantations the biggest drivers of loss and fragmentation.

The first is migratory animals — these need to move seasonally to obtain resources. Second are animals that are fewer in number and require large home ranges, such as grizzly bears and tigers. And third are specialist animals that have very specific needs and don’t do well in altered environments — animals like orangutans, tigers and salamanders.

Ecologist Jodi Hilty, president and chief scientist of the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative (Y2Y), on the animals most at risk from habitat fragmentation

Take action now

Do you want to have a direct impact on climate change? Sir David Attenborough said the best thing we can do is to rewild the planet. So we run reforestation and rewilding programs across the globe to restore wild ecosystems and capture carbon.

Get involved

What are Wildlife Corridors?

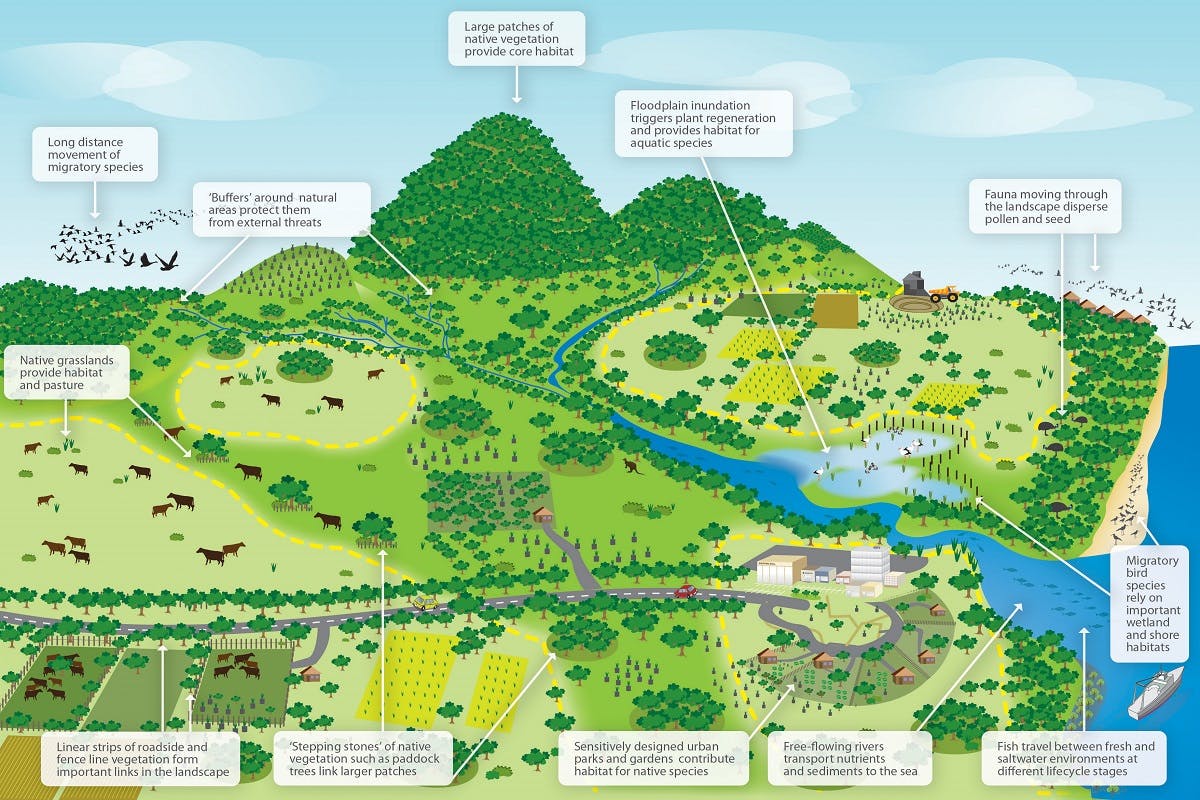

Wildlife corridors are one strategy designed to help nature deal with fragmentation. With habitat range size a strong predictor of species’ vulnerability to extinction, wildlife corridors help to link areas of wilderness together, thus creating larger spaces overall (Beyer and Manica, 2020). They assist in retaining, restoring, and managing natural connections and interactions across landscapes, whilst providing vital spaces for plant species to reside in and animal species to move through, find food, or shelter within.

Wildlife corridors are also known as biological corridors, green corridors, or habitat corridors. We can think of them as belonging to two main categories:

Natural corridors

Naturally established corridors have been created by natural circumstances and may have specific geographical features such as mountains and dense forests. They might be entire expanses of land like plains or prairies; specific forest ecosystems such as tropical, temperate, and boreal forests; or even a flowing water habitat which includes a river and its banks, also known as a riparian ribbon.

Manmade corridors

Man-made corridors have been established by humans for supporting and maintaining biodiversity across many different environments. The most common man-made corridors are the over and underpasses that were invented to avoid animal and human collisions via roads, but they also include smaller versions such as hedgerows on the edge of rural farmland.

There are two specific types of wildlife corridors:

- Continuous corridors are large, unbroken strips of green corridor that lead to another habitat.

- Stepping stone corridors are small patches of habitat that are connected by smaller wildlife corridors.

The purposes of Wildlife Corridors

Wildlife corridors have three main purposes/effects in order to stabilise populations of species within local environments:

- Colonisation: species are able to move and occupy new areas in search of resources such as food, water and shelter.

- Migration: species that relocate seasonally can do so safely, effectively and without humans impeding their pathway (or vice versa).

- Genetic diversity: species have more mating options, which strengthens the overall population and reduces inter-breeding.

There are three types of corridor according to their size:

- Regional (>500m wide): connecting major land masses such as migratory pathways.

- Sub-regional (>300m wide): connecting larger vegetated landscape features such as ridgelines and valleys.

- Local (some <50m): connecting remnant patches of woodland, marshes, and wetlands.

In general, a corridor needs a minimum width of 15m to provide adequate habitat for species to use as a travel lane or for food, nesting or escape cover. Yet some species may stay longer than others as there are different users of wildlife corridors: passage users and corridor dwellers. This indicates how long it takes a species to move through a corridor and sometimes (depending on their size and needs) certain species will make it their permanent home.

The benefits of Wildlife Corridors in action

Species known to use wildlife corridors include deer, elk, moose, bears, mountain goats, lizards, tortoises, sheep, wolves, big cats, and elephants. From the smallest insects to the largest land mammals, the meekest prey to the most cunning of predators; wildlife corridors can help species find food, sanctuary, and safe passage to a new home. Here’s just a few examples of wildlife corridors in action:

The Bee Highway in Norway was constructed in 2014 by the urban guild of beekeepers: ByBi. The “pollinator passage” stretches from Holmenkollen in the north west, to Lake Nøkkelvann in the south east. This project initiated measures such as green roofs, flower-emblazoned cemeteries and strategically placed beehives to make it possible for the bees to find resting places and food almost anywhere in Oslo.

The American Flyways signify the 4 unique aviation routes of migratory birds across the whole of the United States: the Pacific, Central, Mississippi and Atlantic Flyways. Birdlife International is working to help the 350 migrant species that breed in North America and head south for winter by creating lasting conservation partnerships across national borders.

In Australia in 2017, the Rainforest Trust established a 173.5 acre called the Misty Mountain Nature Refuge. The corridor is vital for animals (such as the near threatened Lumholtz’s Tree Kangaroo) to move freely between two large expanses of World Heritage rainforest. The trust is currently installing 17,000 locally sourced plants over the next two years to widen the corridor.

Criticisms of Wildlife Corridors

Some scientists have argued that there is insufficient data on corridor use by animals to conclude on their benefits and the current evidence is inadequate to say whether wildlife corridors serve to increase biodiversity.

One negative aspect, potentially overlooked, is that corridors often allow for the passage of invasive species which can drastically change the ecosystem of a nearby area that was once inaccessible.

Also, wildlife ecologists need to consider “The Edge Effect” - a phenomenon which occurs around the edges of ecosystems, where more light can reach and as a result enables more photosynthesis and plant growth. Border animal and plant species thrive here, and yet, when more edges are created, more changes occur. This can be interpreted as positive or negative, one such negative impact of the edge effect is more competition between species.

Successful Wildlife Corridor stories

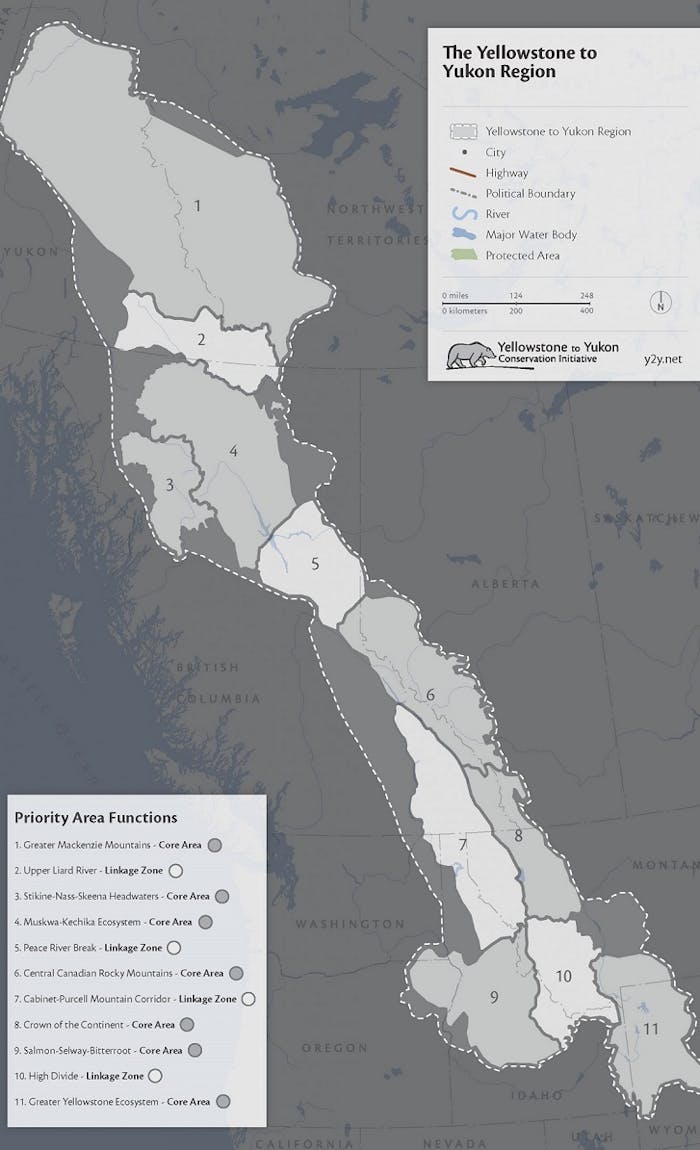

One of the biggest success stories of wildlife corridors has to be the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative (Y2Y). This impressive 2,000 mile (3,200 kilometre) stretch connects Canada’s Yukon Territory to the Greater Yellowstone ecosystem via North America's Rocky Mountains. More than 450 partner groups have joined forces since 1993 to support the shared mission and vision of creating an interconnected system of wild lands and waters, harmonizing the needs of people with those of nature.

This ambitious cross border corridor features several natural ecosystems; housing wolves, wolverines, lynx, cougars, golden eagles, and bull trout; with one of the connections allowing grizzly bears to naturally re-occupy the Salmon-Selway wildland complex in central Idaho. Saving wildlife and humans from road collisions is a key part of the project as the region already has more than 100 under and overpasses.

As well as protecting the area to maintain and restore habitat integrity, Y2Y seeks to support environmental and social justice and oppose actions and policies that undermine human diversity, equity, and inclusion principles.

Failures

When wildlife corridors become so minimised they are no able longer to support the passage of animals. This is the case for Florida’s wild spaces. This is a state known to be the origin of the Walt Disney empire: an empire which has pushed the natural environment to almost breaking point. The Florida Wildlife Corridor organisation is on a mission to accelerate conservation in Florida by 10% annually to protect 300,000 acres within the corridor by the end of 2020.[1]

Every day 1,000 new residents move to Florida and each hour 20 acres are lost to development. The roads that are built, like Interstate 4, block wildlife and water. For creatures such as the Florida black bear and the Florida panther, soon there will be nowhere to go. Without long-term protection, significant portions of the Florida Wildlife Corridor are at risk of further fragmentation – either by roads or other development - and will prove detrimental to Florida’s freshwater resources and ultimately harmful to plant and animal communities.

The ‘Last Green Thread’ is a powerful short film following three friends as they set out on an expedition into the most rapidly developing landscape in Central Florida, traveling the most vulnerable wildlife corridor in the state.

Natalie Fox on The Last Green Thread

Do Wildlife Corridors actually work?

Although public opinion, conservation groups and conservation policy may appear supportive of wildlife corridors, biological scientists have long argued the pros and cons. Whilst this has already wasted precious time, especially at the rate we are losing habitats and species, a recent study which concludes 18 years of research, could serve to end the argument once and for all.

Using long-term data from a large, replicated experiment, Damschen et al. (2019) show quantitatively how corridors reduced the likelihood of plant extinction in patches by about 2% per year and increased the likelihood of patch colonization by about 5% per year. Connected patches had 14% more species than unconnected patches. The study concludes: “Restoring habitat connectivity may thus be a powerful technique for conserving biodiversity, and investment in connections can be expected to magnify conservation benefit.”

With robust science backing up the notion that connectivity is key in ecosystem health and biological diversity: what lies ahead? Typically, investment in wildlife corridors has been minimal, yet when we think about the future, we must consider the increasing pressures climate change will have on our Earth’s biodiversity. Wildlife corridors have been suggested by the Australian government as a strategy to contribute to the resilience of the landscape in a changing climate and help to reduce future greenhouse gas emissions by storing carbon in native vegetation. Not only could more wildlife corridors help strengthen biodiversity, but they could be an important part of climate change mitigation.

How to support Wildlife Corridors

- Find out where your local wildlife corridors are, what purpose they serve and how you can protect them. Local conservation organisations should be able to help.

- Turn your garden into a miniature wildlife corridor. Providing hedgehogs hostels, bee hotels and bird houses can support migratory and stationary local species.

- What local ecosystems could be connected in the areas you live in? Are roads nearby responsible for killing wildlife? Are species you’re used to seeing starting to be less visible? Could you help local conservationists to identify and preserve passages for wildlife? Finally, could you help increase biodiversity in your local area by fostering design principles of wildlife corridors?

Sources & further reading

- “Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES)” - The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES)

- “Nature’s Dangerous Decline ‘Unprecedented’; Species Extinction Rates ‘Accelerating'” - The United Nations

Increased movement between isolated populations

Increased movement between isolated populations