The aims of rewilding resonate with a lot of people. Our rewilding projects are a way to translate this enthusiasm into concrete actions that restore degraded ecosystems, enable ecosystem processes or enhance biodiversity. We have developed a rewilding project development process that aims to ensure that our members' support has the greatest possible impact. Here, we let you in on this process so you can understand how we work and feel confident that these projects are worthwhile.

What does rewilding mean to us?

Rewilding to us means restoring degraded ecosystems, enabling ecosystem processes and enhancing biodiversity.

Who's behind our projects?

Broadly speaking, we can divide Mossy Earth projects into two broad categories: Mossy Earth funded projects and Mossy Earth led projects.

In many of our rewilding projects you’ll see us working with different local conservation organisations, helping them fund on the ground activities such as Red Kite reintroductions. Alongside these, we are also starting to develop projects led by our own conservation biologists with the vision of creating what we like to call our rewilding hubs. An example of this is our Native Oyster restoration project in Scotland, and there are more in the pipeline!

Objectives

To be suitable, the project must aim to achieve one or more of these objectives that are central to rewilding:

- Restore biodiversity and/or abundance of native species

- Restore key ecosystem processes (e.g., flooding, migration, herbivory, predation)

- Improve habitat integrity and connectivity

- Protect unique and threatened ecosystems and species

We seek projects that:

- Can achieve outcomes that are stable in the long term. This means intervention rationale has to be sound from an ecological perspective but also that the project is sustainable in a socio-cultural context through stakeholder participation and engagement where relevant.

- Carry out interventions that are well supported by existing evidence and/or are designed in such a way that allows the effectiveness of such interventions to be tested.

Additionally, we also consider whether projects add value in other ways that go beyond their primary objectives such as:

- Generating knowledge or innovation that opens the door for larger scale and more cost effective interventions in the future.

- Achieving broader socio-economic and environmental benefits, such as:

- Providing economic value to local communities (e.g. by promoting ecotourism or providing ecosystem services).

- Protecting local communities from the negative impacts of invasive species, extreme weather events, soil degradation and desertification.

- Sequestering carbon.

Rationale behind our rewilding projects

Is the ecological problem and proposed solution supported by sound scientific evidence and ecological theory?

Interventions on an ecosystem can have cascading consequences on many species and processes. This is exactly the reason rewilding projects are a powerful tool for restoration. However, this complexity often makes it difficult to predict the impact of an intervention. Therefore, a good rewilding project will back up predictions with scientific evidence and acknowledge remaining uncertainties.

If the rewilding project aims to implement a novel intervention for which there is limited empirical evidence, the rationale should be based on ecological theory and properly referenced. In this situation, it is crucial to evaluate unwanted impacts and how to deal with them should they occur (see adaptive approach below). Although it may be tempting to focus only on scaling up well studied interventions, we think innovation is necessary if we are to reap the full potential of rewilding. Therefore, we also value well thought out research projects that will provide the evidence we need to make rewilding efforts more effective.

In all cases, we also consider what would happen if we did not support the project to understand if there really is a clear cost of inaction. By assessing additionality in this way, we can assess the positive impact of the actions we undertake with the support of our members.

Our vision

Does the project fit with the rewilding goals of Mossy Earth?

Since the early days of Mossy Earth, we have been trying to identify and implement actions that achieve the greatest possible impact to restore nature with the funds we have available. Every rewilding project we undertake or support we do so with the big picture in mind. As a team, we set out our rewilding goals and priorities for the year and use this to guide our research and management decisions. Our vision is based on two key principles : Maximising diversity & Maximising impact

We strive for a diverse portfolio that spans countries and themes. This helps ensure that our members’ impact reaches across ecosystems, landscapes, and species. It also allows us to raise awareness about a wide array of ecological issues and make interesting connections, maximising opportunities for learning. That said, in order to deliver robust and well thought out projects, we don’t want to spread ourselves too thin so we prioritise areas and types of projects. Firstly, we prioritise projects at our rewilding hubs in the United Kingdom and Iberia where our biologists are based. They understand the local ecosystems and cultural landscape, and can be more involved in or run the projects directly. We also prioritise projects we think will provide our members with the biggest bang for their buck. We prioritise rewilding projects that help combat climate change, have cascading impacts across ecosystems, and/or save threatened but under-funded species from extinction. In general, we only support projects that make sense within the context of our rewilding vision.

Project Development Protocol

As we continue to grow, we are working hard to make sure we have the systems in place to work towards our vision at scale. To achieve this, we have distilled what we have learned so far and poured it into a new project development protocol designed to ensure that:

1. We gather good project opportunities.

2. We have an effective process to select which of these opportunities to focus on.

3. We develop a project management plan that is robust but not overly time consuming for our partners.

4. We generate and use scientific evidence effectively.

This protocol, which we outline in more detail here, takes project ideas from their origin through to assessment during which we gather key pieces of information that allow us to score them and use a multi-criteria analysis to compare to other opportunities. If a project passes this assessment, this then leads on to planning, through to implementation and monitoring, and ultimately evidence sharing. Below we discuss two of the criteria we consider in relation to project design:

Outcome stability

Are the actual drivers of ecological degradation addressed?

For projects to be successful in the long term, it is important that the problems that led to the original issue are addressed. For example, efforts to reintroduce a top predator in an area where its demise was the result of a declining prey population are bound to fail if prey numbers don’t increase. Similarly, if human-wildlife conflict was the issue that originally drove a species away, measures must be in place to mitigate this problem.

Additionality

Will Mossy Earth funding be essential for the project to go ahead?

To ensure we achieve as much as possible with the funds we have, it is not enough to know the ecological outcomes of what we do. To understand if our support was truly needed, we also must evaluate the likelihood that these outcomes would be achieved even if we did not get involved. Part of this comes down to the issue we are focusing on. Projects that tackle neglected problems such as the plight of less charismatic organisms or promising but unexplored opportunities tend to have greater additionality.

Another important angle is to consider the funding structure and the likelihood of there being alternative sources of funding available to implement the project. When the total project budget is covered by us, we can be more confident that our involvement was decisive. However, we also establish co-funding partnerships with other organisations when this allows for more ambitious projects to be implemented than if everyone worked separately. This is often important to get larger projects off the ground, such as species reintroductions or those that require considerable engineering or construction work, for example dam removal or wetland creation.

Implementation & monitoring

We work independently or with our partners to design a management plan for each project, where we outline the project objectives, activities, timelines and expected outputs. Within this document we also delve into matters such as cultural considerations, stakeholder engagement and wildlife ethics. This document forms the foundation of our management decisions throughout the course of the project.

Also included within the management plan is the monitoring strategy. This includes details about how and when monitoring activities will take place to find if project outcomes are being achieved. However, the type and extent of monitoring varies widely from project to project. In some cases baseline surveys and ongoing monitoring are needed to inform the intervention itself while in other cases monitoring is only required to evaluate the success of the project. In each case, we have to compare the value of the information we obtain through a monitoring activity against the impact we could achieve if we allocated the same funds elsewhere. Achieving this balance is no easy task but, broadly speaking, the extent of monitoring should increase as:

- The uncertainty around the effectiveness of the intervention increases. In these cases, fewer assumptions can be made about expected outcomes and a more thorough monitoring approach is likely to generate information which could be of benefit to similar projects in the future.

- The budget increases leading to greater financial risk.

- The probability for unintended consequences is high because of ecological or social risk(s).

- The need for monitoring to inform decisions increases (adaptive management).

This should help us avoid two wasteful traps that can often beset projects:

- Carrying out interventions for which there is limited evidence that they will be effective without having a sufficiently thorough monitoring approach to determine if it was effective or not - a trial designed in a way that allows for scientific inferences to be made would be more appropriate.

- Spending large amounts of time and money on monitoring an intervention that is tried and tested and for which there is already ample evidence demonstrating it will be effective - a simpler plan using some key indicators or proxy measures would be more appropriate.

In our Conservation Evidence methodology you can learn more about how this fits into our approach to using and generating evidence.

Transparency

Once a project has started we do our best to take our members on the journey that is the implementation of an exciting rewilding project by:

- Creating one short video interview, otherwise known as a project podcast, with the Mossy Earth biologist in charge to introduce the project to members. We will then select some projects for in depth YouTube videos that you can find on our channel.

- Keeping members up to date with the progress and sharing impact cards whenever there is an on-the-ground action, cost or project pot contribution (when we set aside money for a project) through the membership account.

- Updating members on our projects in personal, in-depth feed posts on the membership account and sharing monthly field reports via email.

- Helping people get a better perspective of how our rewilding projects are financed by sharing a quarterly report. Members are also given the opportunity to answer key questions on our rewilding projects in regular membership votes. Learn more about all our transparency measures in our trust and transparency methodology.

- Making sure that all on-the-ground activities, expenses, and summary metrics about our impact are detailed on our newly launched transparency dashboard.

To make sure we are kept up to date with project outcomes, monitoring and spending, we have created a reporting template to be used by our project partners to construct either a progress report or a final report depending on the project timeline.

Technology

A significant amount of our rewilding work relies on the use of technology. Some of the tools we commonly use in our projects are camera traps, GPS tags, environmental DNA (eDNA) and drones.

Camera traps are a non-invasive tool, placed systematically or randomly in the field to capture images or videos of the local wildlife or target species. These cameras can be used to gather species lists for an area, species richness estimates, behavioural data and even estimates of population size.

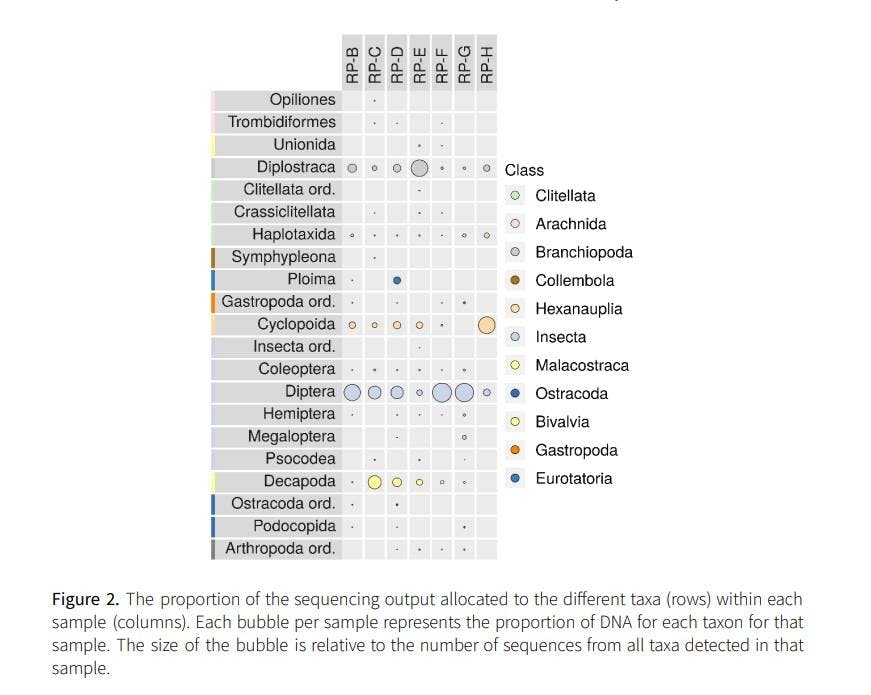

As organisms interact with the surrounding environment, they leave traces of their DNA. This is known as eDNA, and it can be collected from samples of freshwater, saltwater, soil and even air. An emerging and valuable tool, it can be used to detect organisms that are difficult to find using other methods. We’ve used it to detect invasive species and establish invertebrate and vertebrate diversity within lakes and ponds at a rewilded mining site in Portugal, amongst other things!

We are also using drones to create high resolution maps that can provide very useful information about the ecosystems we are working to restore. For example, we have used them to monitor plants in hard to access locations, map potential snail habitat and assess the spatial arrangement of termite mounds and trees across the landscape.

All of this technology is very exciting and can be very useful, but it can also be a distraction if not used well. This is where our approach to using and generating evidence comes in which you can read all about in our Conservation Evidence methodology.

Improving how we use and share evidence

One of the challenges in nature restoration is that ecosystems are very complex, and we often must integrate different kinds of evidence to come up with interventions that work. For a given decision, evidence may come from peer reviewed papers, databases, project reports, practitioner and expert knowledge, local and indigenous knowledge and citizen science to list some of the sources.

We decided to tackle this challenge head on by setting up a partnership with Conservation Evidence, an ambitious project that aims to provide a “free, authoritative information resource designed to support decisions about how to maintain and restore global biodiversity”. We will be working with their team, based at the University of Cambridge, to improve the way we use and create evidence about our projects. Here are some of the reasons we are very excited about this:

- Better use of evidence can improve project outcomes.

- Using more structured approaches to decision making will make it easier for us to share the rationale behind them and get feedback from our members and project stakeholders.

- Improving our approach to cost reporting will help us better track the cost-effectiveness of our work. This can also prove useful for other organisations pursuing similar projects or for seeking ways to reduce costs.

- Optimising how we create and share new evidence through our projects will help us ensure that we are not only having a direct impact on these ecosystems but also creating a knowledge base that will inform future projects.

- Finally, by making progress in this direction, we hope to inspire other organisations to do the same.

We will keep updating this page as we make progress towards these goals.

Sources & further reading

- “Rewilding European Landscapes” - Springer Link

- “Feral: Searching for Enchantment on the Frontiers of Rewilding” - George Monbiot