- Trees planted: 59,325

- Status: Implemented

This reforesting Scotland project aims to restore a diversity of woodland types to Scotland, prioritising the pinewood and riparian woodland habitats. Scots pine and downy birch saplings, alongside a diversity of food-producing broadleaf trees, such as hazel and bird cherry, are being planted across the valley bottoms and hillsides, while alders, downy birch, willows and other important riparian tree species are being planted alongside degraded riverbanks.

Project Timeline

Spring 2024

1,750 trees planted at three different sites in Renfrewshire- Formakin Estate, Easter Kaim and Meikle Garclaugh.

Autumn 2023

650 native trees planted at 2 sites in Renfrewshire.

The Ecosystem

Tree species

We plant Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris), downy birch (Betula pubescens), juniper (Juniperus communis), hazel (Corylus avellana), holly (Ilex aquifolium), European crab apple (Malus sylvestris), common hawthorn (Cratageus monogyna), alder (Alnus glutinosa), bird cherry (Prunus padus), Elder (Sambucus nigra) and Wych elm (Ulmus glabra), eared willow (Salix aurita), grey willow (Salix cinerea), goat willow (Salix caprea) and aspen (Populus tremula).

Priority species

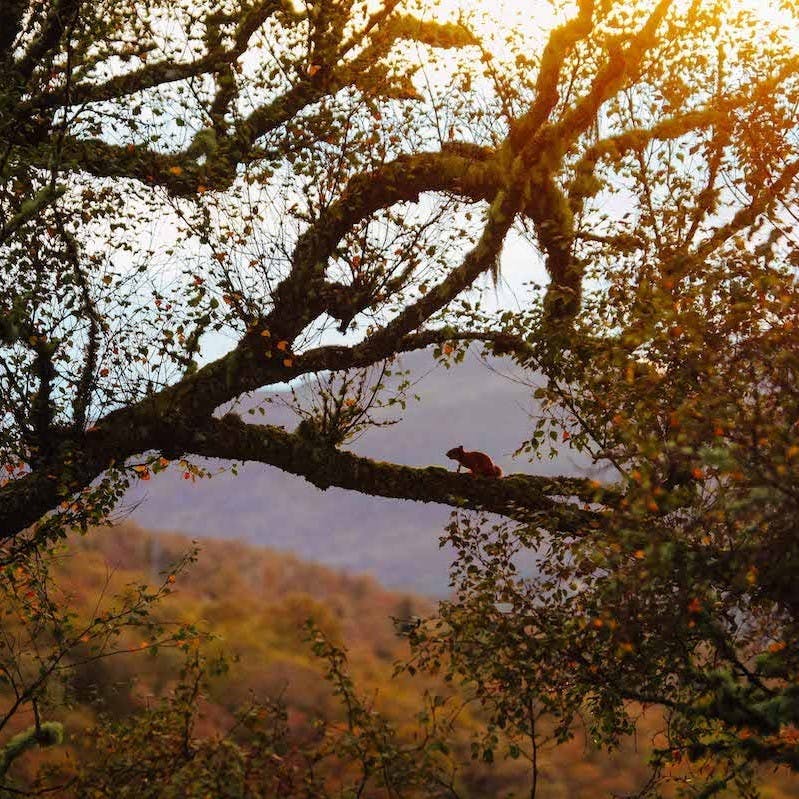

Twinflower (Linnea borealis), black grouse (Lyrurus tetrix), golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos), white-tailed eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla), red squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris), Scottish crossbill (Loxia scotica), pine marten (Martes martes) and Atlantic salmon (Salmon salar) are all present in the area.

An Ancient Wilderness

Reversing centuries of ecological damage

Historically, much of the Scottish Highlands were covered in a forest of majestic Scots pine and colourful broadleaf trees, home to a diversity of plants and animals. Today, the landscape is largely devoid of these unique woodlands and many of the species that once thrived here have been lost. Our aim is to undo some of this damage and restore the empty glens and rewild the Scottish Highlands to rich, biodiverse, wild woodlands.

Unique pinewoods

What makes the pinewood ecosystem special?

The Scottish pinewoods are a globally unique habitat due to the absence of any other conifer tree, other than Scots pine, within the woodland. These woodlands support some of the UK’s rarest plant and animal species like the beautiful and delicate twinflower, the elusive wildcat and the impressive capercaillie. Restoring native woodlands in all their beautiful complexity will help return Scotland to wilder, richer state that a variety of species, including humans, can enjoy.

Waterside woodlands

What makes the riparian woodland ecosystem special?

Riparian woodlands are rare in Scotland, with much of Scotland's riverbanks devoid of trees. These woodlands are important for stabilising the riverbanks, preventing soil erosion and reducing flooding. They also improve the health of the river by adding nutrients to the water in the form of leaf litter and invertebrates and creating shelter and shade for wildlife. This is vitally important for Scotland's fish species, particularly salmon and brown trout, which are threatened by the rising water temperatures brought on by climate change.

The Threats

Climate change

At the end of the last Ice Age, much of the Scottish Highlands were covered in woodland, mainly composed of Scots pine and birch. Around 4,000 years ago, the climate began to change. The natural tree line lowered, peat bogs expanded and woodland cover began to decline.

Deforestation

At around the same time, humans began to significantly change the landscape around them. Trees were felled to make room for crops and graze livestock, to harvest timber and fuelwood. By the 1700s, the great Caledonian Forest was reduced to small, isolated pockets of the Highlands. Much of the wildlife that thrived here, like lynx, bears and wolves, were lost.

Overgrazing

In the 18th and 19th century, when much of the landscape had already been cleared of forests, estate owners began to clear the land of people. Known as the Highland Clearances, local people were forcibly evicted from their homes, entire villages were cleared, to make way for sheep grazing. Today, a combination of sheep farming, unsustainable numbers of deer and intensive land management for sporting purposes is restricting the ability of native woodlands to regenerate on their own. Reforestation with native species is therefore vital to restore this unique habitat.

Reforesting Scotland

Tree planting at Alladale Wilderness Reserve, which is part of the national breeding programme for wildcats and has successfully bred several litters of wildcats in recent years.

Community Tree Planting at Formakin Estate

Volunteers from Outdoors for you helped plant 200 trees at Formakin Estate, November 2024.

Easter Kaim

Tree planting at Easter Kaim in February 2024.

Kyle of Sutherland

This update (November 2024) shows our planted trees growing and filling the gap between the previously planted trees and the river. There's a very good establishment rate around the site, only the birch seems to be struggling, which is likely due the drought of May/June 2023. However, there are plenty of older birches around and enough alder and willow to create the shade needed.

Our Wider Rewilding Aims

To compliment our reforestation efforts and work towards our wider ambitions of building a more resilient natural world in Scotland, we have supported the following rewilding interventions: native oyster and seagrass restoration, temperate rainforest restoration, the mountain birch project, riparian restoration, monitoring of Atlantic salmon, restoring aspen trees, surveying freshwater pearl mussels, monitoring wildlife, montane scrub survey at Alladale Wilderness Reserve, and the construction of eagle nest platforms.

the team behind the project

Hannah Kirkland, Conservation Biologist at Mossy Earth

Innes MacNeill, Reserve Manager at Alladale Wilderness Reserve

Planting Team at Alexander Forestry

Sources & further reading

- “This is the potential CO2 sequestered in above ground biomass in the Scottish Highlands over a period of 100 years” - Trees for Life

- “Rewilding–a new paradigm for nature conservation in Scotland?” - Taylor & Francis Online