- Management Plan

- Status: In Progress

Around 400,000 hectares of exotic eucalyptus tree plantations are estimated to be abandoned in Portugal and no longer providing a source of income to landowners. This represents a huge untapped potential for ecological restoration of large areas of forest, particularly in Portugal’s southwest, which is home to a special diversity of oaks (Quercus spp.) and many other endemic flora & fauna species currently under threat.

We aim to develop low impact and cost-efficient techniques to remove eucalyptus from abandoned plantations and boost natural regeneration to take its place, advancing succession into mature oak woodlands.

The project starts in the Mira River valley, impacting the wider goal of recovering the river’s ecological corridor functions, as a part of our large-scale restoration project for the whole Mira hydrographic basin. Our goal is to make this a replicable methodology to scale in other territories.

Project Timeline

Autumn 2024 - ongoing

Monitor biodiversity through different angles (i.e soundscape), measuring several environmental parameters to evaluate results and adapt the plan accordingly. By 2025, we aim to have secured more landowner contracts, extending the project area in the ecological corridor of the Mira River.

Autumn 2024 - Winter 2025

Carry out interventions to eradicate eucalyptus using contracted specialised forest operators. The first plot serves as an experimental site to test and improve techniques before scaling elsewhere, showcasing to other landowners what can be done in terms of ecological restoration and the associated benefits.

read moreA True Ecological Corridor

Our objective to convert neglected eucalyptus stands to native forest will start in the valley of the Mira River - a true ecological corridor between two important Natura 2000 sites - Costa Sudoeste and Monchique (both under the Birds and Habitats Directives). Situated between Portugal’s southwest interior and coast, it is in itself a major biodiversity hotspot of Mediterranean biomes.

Declining native woodlands

The riverine hillsides of the Mira River valley present a great opportunity to restore the native but declining woodlands in Portugal’s southwest. The area is dominated by the Portuguese oak (Quercus faginea), cork oak (Quercus suber) and even contains the local endemisms - Algerian oak (Quercus canariensis) and Carvalho-Estremenho (Quercus estremadurensis), although both are critically endangered. These forest ecosystems host a significant range of biodiversity, including several other threatened and endemic plant species, such as Senecio lopezii, while the Mira River itself supports very notable freshwater vegetation like the Broad-leaved Pondweed (Potamogeton schweinfurthii).

Home to a diversity of wildlife

In terms of wildlife, most mammals present in Portugal can be found crossing this corridor. Recent reports of red deer (Cervus elaphus) sightings indicate that this important herbivore has reintroduced itself back into the area. The Mira River is an essential refuge for many other species in the south of Portugal, including otters (Lutra lutra), Iberian tortoises (Mauremys leprosa and Emys orbicularis) and endemic freshwater bivalves like Unio tumidiformis. Most notably, it is home to two critically endangered endemic freshwater fish, Iberochondrostoma almacai and Squalius torgalensis, among other threatened ichthyofauna, such as the southern barbel (Luciobarbus sclateri) and the migratory allis species (Allosa fallax) and the European eel (Anguilla anguilla).

Being a passageway for migratory passerines, the avifauna is also abundant and includes several species with protected status such as the little bittern (Ixobrychus minutus), the common sandpiper (Actitis hypoleucos) and various riverine birds species, such as the kingfisher (Alcedo athis).

Key ecosystem services

Restoring these forest habitats and their bordering river gallery will also improve key ecosystem services, such as water filtration for the river, aquifer recharge, soil creation, carbon sequestration, wildfire prevention, genetic reserve, pollination and climate amelioration, which comes both as adaptation and mitigation to climate change by creating fresher swathes in a river basin under desertification.

Eucalyptus in Portugal

Portugal holds the world’s largest relative area of eucalyptus monocultures, an exotic tree species cropped for wood and paper pulp production. These plantations are nationally known for not providing much habitat for native biodiversity or valuable ecosystem services. For example, eucalyptus stands increase the risk and intensity of wildfires, while associated silvicultural practices are often conducive to severe soil erosion and reduced water infiltration, and do not allow for other vegetation to grow in the understory. In parallel, since the Portuguese native fauna & flora did not evolve alongside this allochthonous tree genus from Australia, it is not naturally adapted to eucalyptus monocultures - most animals do not feed on this plant and the allelochemicals it produces can inhibit the growth of other plants.

At a cost for landowners & nature

At the same time, latest data informs that almost half of the eucalyptus plantations are currently abandoned in the country, since productivity greatly declines after a few harvest cycles while the costs of reconverting it to a better land use are high. This is due to the eucalyptus species’ continuous re-sprouting behaviour after each cutting, leaving trees in the form of many thin stems stretching from each stump, concomitant to the fact that extensive stump uprooting is quite expensive and often leads to extensive soil erosion. Additionally, after a full production cycle, the soil in these stands is usually exhausted in nutrients and water. As such, large areas are left neglected and stagnant in their ecological potential which could be native forests instead.

Removing the burden

The starting point for this project is the surrounding habitats of the Mira River, where pockets of relict autochthonous forest subsist disturbed by old-age eucalyptus plantations, which are devaluating the whole riverine ecosystem. By releasing these lands from the persistent eucalyptus, we will open the way for natural regeneration to emerge and thrive. In turn, we hope to see an increase in the occurrence of the many rare and endangered species aforementioned as the size of Iberian Southwestern oak woodland habitats that sustain these species increases and as habitat connectivity improves.

Developing scalable solutions

By piloting these interventions in the Mira Basin, we are looking to simultaneously develop low-impact and cost-efficient techniques that could truly scale Mediterranean oak woodland restoration using neglected eucalyptus stands. Thus, it is also a bridging investment for finding replicable solutions, enabling more forest operators on the ground to pursue this possibility and inspiring more action in other territories.

Our Project Plan

The practical rationale for this project is to develop our low-impact methodology for eradicating eucalyptus from plots to allow for natural regeneration and the recovery of native forests. The goal is to see the forest improve in terms of habitat structure and biodiversity and its former function alongside the Mira River as a crucial ecological corridor.

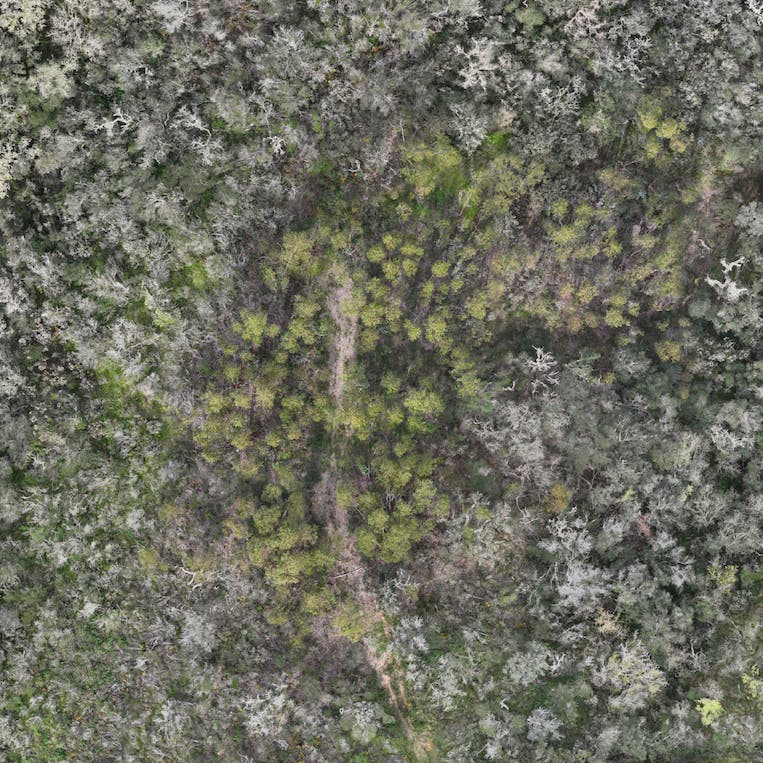

To achieve this, firstly we are running a pilot intervention on a 46.5 ha plot of riparian area in the municipality of Odemira on the Mira River, containing approximately 20 ha of eucalyptus stands. Using this as an experimental plot will allow us to test and improve techniques, whilst serving as an example of ecological conversion of eucalyptus stands to showcase to other potentially interested landowners.

Here are a few techniques that we are considering at the moment:

- Arborism pruning: to cut down tall eucalyptus trees so logs do not simply fall down on top of young regenerating oaks. Instead they will be chopped and lowered in a controlled manner.

- Horse logging via existing paths: to transport tree trunks out of the heart of the forest without using heavy machinery and causing too much damage to vegetation.

- To exhaust the eucalyptus stumps, there will be frequent follow-up control of new shoots from the pruned stumps until resprouting eventually stops.

Since this first plot is bordering the river, we will care for the restoration of the riverine forest too. In this case, that means eradicating a clump of the invasive Giant reed, Arundo donax, that exists in a small area. We will have to dig out all the rhizomes and roots to prevent further invasion. We will also immediately install an erosion control structure with wooden poles, planted with bundles of the native reed, Phragmites australis.

See this Project Management Plan for an extensive description of the assessment and implementation plan. Included in this document is a monitoring plan and evidence on the state of the habitat prior to this intervention. The process of gathering a baseline scenario has involved:

- Pre-study on the current conditions of the pilot plot

- Field-assessment of flora

- Installation of camera traps in key crossing points of the property for wildlife.

- We are also looking into testing a soundscape monitoring method to capture 'before and after' samples. Additionally, we will measure environmental parameters such as soil organic matter, soil moisture, air temperature amongst others.

All this data is to be analysed and evaluated to understand if we are achieving the expected results, or if not, to learn and adapt our strategy if necessary whilst communicating the outcomes.

In a more mature phase of the project, we aim to carry out on-site training and knowledge transfer activities for interested representatives of any stakeholder groups and to expand the project to more plots alongside the Mira River.

Eucalyptus removal work begins

An update from the field in March 2025.

The wider context of this project

This project is a part of our broader restoration efforts in the Mira River Basin.

The Mira Basin in the southwest of Portugal is a biodiversity hotspot comprising a variety of terrestrial, freshwater and marine Mediterranean habitats. In this area, one can find a quarter of all Portuguese flora (more than 800 taxon of vascular plants, of which 35 are threatened and 40 are local endemisms), more than 270 species of birds, threatened endemic fish species and most mammals, reptiles and amphibians existing in the country.

Current challenges

There are current environmental-socio-economic issues, that are quite representative of the Mediterranean, heaping pressure on and resulting in an overall decline of wild habitat areas from:

- climate change inducing desertification

- invasive species and pests

- wildfires

- intensive agriculture competing with nature itself for land and water resources

- intensive silviculture (i.e. eucalyptus monocultures)

- land abandonment, degradation and poor land use practices

- harmful touristic activities on coastal ecosystems

These have created, in parallel, the right momentum for large-scale direct restoration as demanded by local people for action and solutions in reference to the “water wars" or "wildfires”, which translates into fertile ground for such a project from a social perspective. The perceived need and openness from institutions and landowners is an opportunity to tackle land abandonment and ecological degradation through interventions such as this neglected eucalyptus stands project.

We are focusing on the Mira Basin as one of our landscape scale restoration hubs for its natural richness, the threats it faces right now but also its great potential to become a model for ecosystem restoration and the creation of ecological corridors at a landscape level for humanised drylands. Eucalyptus stand reconversion is an important component of this goal.

Partnerships

Udo and Claudia Schwarzer from BioPiscinas Lda are our consultant partners helping with their expert advice on rewilding eucalyptus stands in southwest Portugal’s oak woodlands.

Project Discussion

Hear the in-depth background of this project and gain insights on what we're planning for the restoration of the ecological corridor in the Mira Basin.

Project FAQs

What will happen to the removed eucalyptus logs?

The current plan is to sell the removed logs for its common value - timber. Our first landowner has agreed that this income will be reinvested into the project, contributing to the financial sustainability of the intervention. Another option we are keen on exploring for the future is the production of biochar, which could be put back into the land and help regenerate soil.

Will you be planting trees to bring back native forests?

We are giving nature a shot at doing it on its own terms, because natural regeneration does it better than us. In particular, when there is a strong seed bank in the vicinity or the process has already started. Luckily, this is the case we find in our first plot. We will consider, however, if the circumstances are not so favourable. For example, the restoration of the riverside forest often requires planting riparian trees to factor in the natural competition with fast-growing grasses or even invasive species.

How long do we expect the natural regeneration process to take?

The time taken by nature to regenerate will vary greatly from place to place, depending on the baseline conditions. In the case of our first plot, this process is actually quite advanced, in comparison to the average timescale, since we are working with a long abandoned plantation of eucalyptus. To illustrate this, one can find many Portuguese oaks, cork oaks, ashes, hawthorns, wild strawberry trees and Iberian wild pear trees growing there, some higher than several metres in height already. There are also unpredictable factors, such as climate change, that make estimating the growth of our forest difficult still. Nevertheless, we can estimate that in 50 years time (or probably less), this first plot will look very different, resembling much more of an oakland.

Could you use animals to control the vegetation and prevent fire in the native forest?

Our pilot plot is well protected from fire entry points as it’s mostly surrounded by low-fire risk farmland. Fire behaviour and prevention analysis is a must do in Portugal, with each plot usually having its own plan, defining ecological discontinuities in vegetation so potential fires can be quickly controlled in the most strategic sites. However, the most effective way of controlling vegetation is by far herbivory, either by domestic animals (including neighbouring herds of grazers) or by wild animals, which is the most interesting for us in the context of rewilding. A deeper assessment of the possibilities for more wild herbivorous animals in this region is underway, but for now, we know we’re contributing to increasing the habitat for these species by reconverting abandoned eucalyptus plantations. We’re not introducing koalas to Portugal or other Australian species that are the only animals who feed on this genus. Not only is this forest structure and composition more fire resilient in itself, the whole ecosystem is, since it can host more flora and fauna species, boosting a more complex food chain. For example, there have been sightings of red deer (Cervus elaphus) making a return to this area, which is exciting for both wildfire prevention and forest restoration in these conditions.

Can you ringbark the eucalyptus trees or is that too labour intensive?

It is possible to ringbark eucalyptus and there would be some advantages in terms of saving costs and labour when carrying out the work to cut and transport the logs. However, new shoots will appear from the base of the stump since eucalyptus is a re-sprouting species. Here are the reasons we are not considering that as an option:

In the local context where eucalyptus plantations have average tree densities of around 1000 stems/ha, we would leave a very large amount of tall standing wood (which would eventually topple onto something). Since our main goal is to assist natural regeneration in the understory, this would later become counterproductive for the survival and longevity of emergent oaks, other native trees and slow-growth bushes. Additionally, the fire risk associated with eucalyptus plantations would not be addressed. That's why a main part of our intervention is to find secure and efficient ways of taking down tall eucalyptus trees and removing them from the forest whilst leaving some deadwood, aligned in contour on the forest floor. The other important challenge is about controlling the re-sprouting of eucalyptus. This is something that would have to happen even with ringbarking.

the team behind the project

Teresa Santos Conservation Site Manager, Rio Mira @ Mossy Earth

Udo Schwarzer Biologist @ BioPiscinas Lda

Claudia Schwarzer Landscape Architect @ BioPiscinas Lda

Francisco Sousa, Landscape Architect @ Mossy Earth

João Rodrigues, Conservation Biologist @ Mossy Earth

For most of my life, I've dreamt about bringing native ecosystems back whenever being confronted by a eucalyptus dominated landscape. This project is all about finding a viable way to realise this, which really fills my heart. I believe this sentiment will be felt by many other Portuguese people, and of course so many animals and plants will love this too!

Teresa Santos, Conservation Site Manager @ Mossy Earth