- Management Plan

- Total budget: £94,956

- Budget spent: £62,958

- Status: In Progress

Ocelots are one of the great wild cats of the Americas. These adaptable felines were once widespread across the continent, including the subtropical plains of northern Argentina. During the twentieth century, ocelot populations declined as they were hunted for fur and large swathes of habitat were destroyed. Today, the ocelot is virtually extinct across its original range in Argentina. Consequently, wild areas like the vast wetlands of Iberá shimmer less without this charismatic cat, which plays a crucial role in regulating other species. We are supporting Rewilding Argentina in a pioneering initiative to recover this species in Iberá - the first ocelot reintroduction of this scale worldwide.

Project Timeline

Summer - Autumn 2024

Five ocelots are integrated into the project from the Bella Vista Refuge (Brazil), Chaco and "La Peregrina" (Province of Buenos Aires). The first three that arrived in summer 2024 have successfully complete a period of quarantine. See footage of one of the ocelots, a female named 'Zamba', as she enters the pre-release enclosure in Iberá.

read moreNovember 2023 - February 2025

New individuals, especially females, are to be incorporated into the project from Brazil (Refúgio Biológico Bela Vista) and Paraguay (Refugio Silvestre Urutaú). The first to arrive was Lila from Paraguay in February 2024.

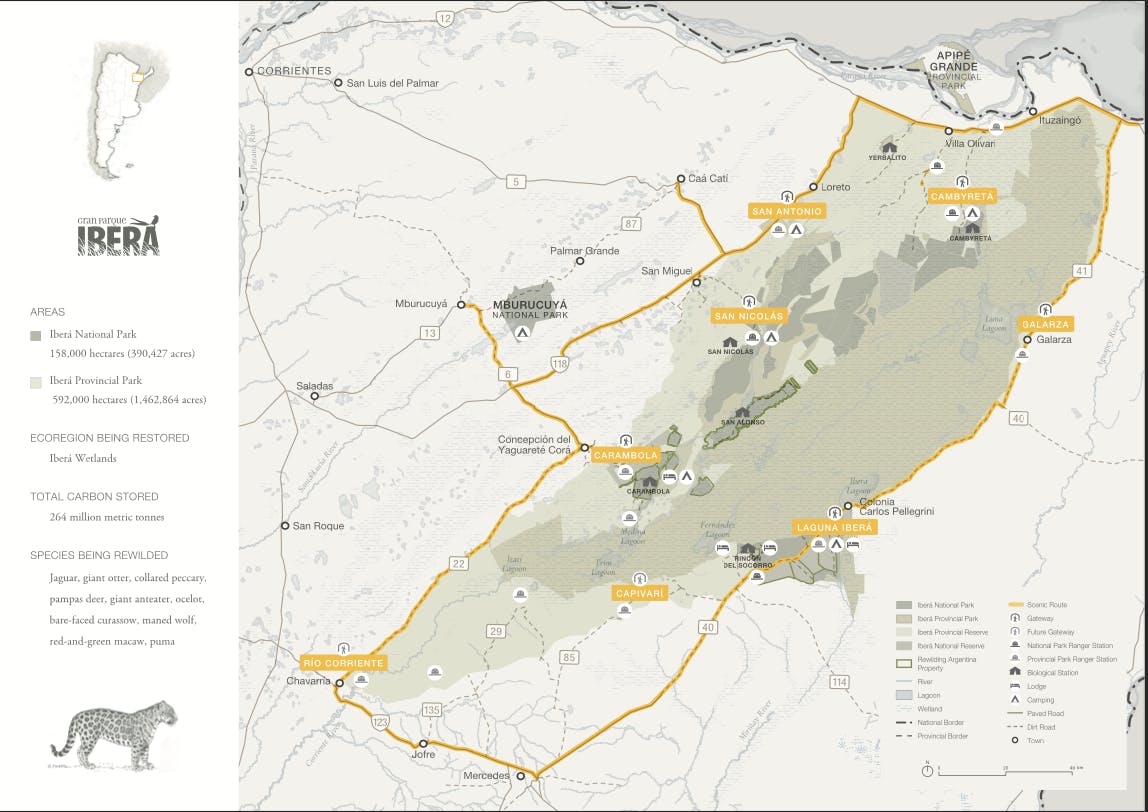

Iberá - the shimmering waters of Argentina

The expansive wetland habitats of Iberá are famed for conjuring up picturesque scenes of entrancing wilderness. The land of ‘shimmering waters’ (‘iberá’ translated from Guaraní) also holds significant value as an area of special conservation interest. It’s situated in the Corrientes Province of northeastern Argentina in the heart of a subtropical plain encompassed by Paraná Atlantic forest, Chaco forest, open grasslands and shrublands.

Within the park’s 758,000 hectares (comprising the Iberá Provincial Park of 600,000 ha and Iberá National Park, of 158,000 hectares) are some of the largest wetlands in South America. An estimated 4,000 species of flora and fauna contribute to the productive ecosystems in the diversity of marshlands, grasslands, forests and open water habitats. Of the many reptiles, mammals and birds, there are caimans, rheas, capybaras, many species of deer, armadillos, foxes, herons, storks and birds of prey. Endangered species such as the black-and-white monjita, the pampas deer, marsh deer, maned wolf, crowned eagle, and a large diversity of Paraná fish also take refuge in Iberá.

Species extinction in Iberá

In the last century, a host of species in the Corrientes Province have succumbed to human pressures, either slipping entirely into extinction or greatly decreasing in numbers.

Habitat destruction driven by factors such as agricultural expansion, and hunting, in which animals were killed for their feathers and fur, led to mass losses of wildlife. Jaguars, giant river otters, tapirs, collared and white-lipped peccaries, giant anteaters, bare faced curassows, red-and-green macaws, and the glaucous macaws went extinct in the wild on a regional, national and sometimes global level. While ocelots, along with pampas deers, maned wolves, lowland pacas, and red-legged seriemas suffered huge declines.

Rewilding at its boldest

Since 2007, Rewilding Argentina (previously operated as CLT-Argentina, an NGO initiated by Doug and Kris Tompkins) has been working to reverse the extinction crisis, restore ecological health and create new economic opportunities in Iberá.

Iberá offers the right conditions to undertake ambitious multi-species reintroductions owing to its vastness and quality of habitats. Within Iberá - the nation’s largest protected area - the threats to animals are being managed. Nature-based tourism is the main economic activity, enticing nature enthusiasts from around the globe to come and observe animals of all kinds in spectacular settings. Surrounding the park, there has been a shift from cattle ranching and forestry towards nature-friendly land use. Members from the surrounding 10 communities are now trained as wildlife guides and work in ecotourism.

Some of the impressive rewilding work already undertaken by Rewilding Argentina has focused on recovering locally extinct or struggling species. In 2021, jaguars returned to the park after being absent for 70 years in a reintroduction project. Corrientes went from having no jaguars to being the province of the Argentinean Chaco with the highest number of this wild cat. Building on this experience and with the help of Mossy Earth funding, Rewilding Argentina has now set out to bring back another important predator - the ocelot.

The Ocelot

Appearance, Diet and Habitat

The ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) is classed as a medium-sized wild cat, but sits only behind the jaguar and puma as Latin America’s third largest feline. With its beautifully patterned coat, the ocelot has an eye-catching appearance for us, but its dark rosettes and spots allow it to camouflage and blend into its habitat. Combined with a slender and agile build, it is well equipped to seek out its prey, which includes small birds, rodents and reptiles among medium-sized mammals, such as brown brocket deer and young capybaras. They are skilful tree climbers and patient hunters, known to wait 30-60 minutes before pouncing on their prey. Ocelots are adaptable species suited to numerous habitats from dry mountains, humid jungles, open grasslands, wetlands and deserts.

Regulators in the ecosystem

Ocelots are mesopredators (medium-sized predators) who play a crucial role in maintaining two important ecological relationships: predation and competition. By hunting prey and competing with or directly preying on other medium-sized predators like foxes, they regulate the abundance of these species, which has a cascading effect on the ecosystem and populations of other species. For instance, the establishment of a healthy ocelot population in Iberá will likely have a positive effect on some threatened species of grassland birds that are currently under high predation pressure from foxes.

The presence of predators also affects behavioural patterns of their prey. In Iberá, one of the expected impacts of an ocelot comeback relates to the grazing behaviour of capybaras. Faced with the threat of predation by ocelots, we can expect that capybaras will spend less time grazing and more time avoiding the predators, which will decrease grazing pressure in a given area and lead to more environmental heterogeneity. Rewilding Argentina is partnering with researchers and universities to study the long-term ecological impact of species reintroduction in Iberá.

The relationship and threats of humans

Historically, ocelots were widely distributed with a range stretching from central-northern Argentina to the southern United States. Appearing in early civilizations through the artwork and mythology of the Aztec and Inca eras, ocelots were respected for their prowess as hunters in the animal kingdom. In more modern times, humans’ can be viewed more as ‘eradicators’ in this relationship. A booming fur trade in the 1960-70s for ocelot hides compounded by an accelerated rate of habitat destruction, caused ocelot populations to severely decline or go extinct in much of their original range. Habitat loss is the main threat that exists today due to deforestation and other human driven factors, such as agricultural intensification.

Ocelots are classified as vulnerable to extinction in Argentina. Small remaining populations have sought refuge in the humid forests and mountains of the north. In the Corrientes Province, only a few individuals have been recorded, being restricted to the extreme northeast of the province. In Iberá, the last sighting came from a camera trap of a single male ocelot in 2015. Without an effort to reintroduce the species, ocelots are highly unlikely to reoccupy Iberá naturally.

Reintroducing ocelots to Iberá

Mossy Earth is proud to be supporting Rewilding Argentina with an ocelot reintroduction project at Iberá park to recover the species. Through funds made available by our members, we are supporting one year of this ambitious 6-year project, the first ever ocelot reintroduction project worldwide.

This component of the project requires the diligent work of the Rewilding Argentina team, which incorporates experts and trained professional, to carry out the following activities:

- Incorporate a minimum of four ocelots into the project (from the project total of 15 ocelots): ocelots to be donated by wildlife rescue centres and zoos in Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay and translocated to Rewilding Argentina’s quarantine centre.

- Ensure the animals meet the necessary sanitary standards for eventual release: involving health checks, analysing biological samples, managing any treatable diseases and verifying the animals are disease-free.

- Conduct the rehabilitation of animals within pre-release enclosures after the quarantine period ends, in preparation for their release: through placing the animals in pre-release enclosures to replicate their natural environment; incorporating live prey into their diets until the animals exclusively hunt for food; and facilitating mating encounters to produce offspring. The possibility of releasing females with their cubs will be evaluated. Individuals that show strong breeding capabilities during their time in captivity will be released to bolster the number of births and improve the self-sufficiency of new populations.

- Release a minimum of 4 individuals into Iberá park: between 4 to 6 individuals from the pre-release pens during two release periods during the year.

- Monitor the adaptation of the animals post-release: the ocelots are to be fitted with GPS telemetry for tracking, which will monitor and assess their movement, acclimatisation and hunting ability. The animals will be supplemented with food if necessary and retrieved/assisted in the case they fail to hunt or require medical care. Long-term monitoring will continue to ensure animals’ survival and register reproductive events post-release.

To reach a self-sustaining population of ocelots in the park, the genetic variability of the reintroduced animals will be studied 4 years following the project’s completion. Based on the results, further interventions will be carried out if needed to improve genetic diversity.

Promoting peaceful coexistence

There are potential risks of ocelot reintroductions for which this project has mitigation measures in place. In the case of the ocelots dispersing into populated areas, there is a possible threat to livestock and poultry. To address this, proactive measures include engaging with farmers prior to the release and promoting abundant wild prey for the ocelots. Reactive measures will involve adjusting husbandry practices and implementing night hours enclosures for livestock and poultry.

Within Iberá park’s 758,000 hectares, the threats to the ocelots are either absent or minimal. Poaching is absent, extractive activities are almost non-existent and there are no permanent residents living in the park.

Taking a comprehensive approach to preparing for and adapting to post-release scenarios is essential in promoting a peaceful coexistence. The goal is to minimise risks for the local community, protect domestic animals and prevent conflicts.

Pioneering ocelot reintroductions

Reintroduction programs are not a common conservation/rewilding strategy in South America. As a consequence, the supporting administrative processes are often cumbersome or entirely lacking. This represents a hurdle for this project to overcome but in doing so, it aims to pave the way for future species reintroductions on the continent.

The experience and knowledge generated through this project will be used to improve reintroduction techniques for the ocelot. Results and methodologies will be published in specific bulletins, similar to those used by the IUCN. Additionally, a reintroduction protocol for ocelots will be drafted to be used by governments and organisations in Argentina or other countries interested in the species recovery. There will be an extended invitation to the field to learn from the project.

Part of this project’s vision is for Iberá to become a source of species to launch reintroductions elsewhere in the world. Already, there is expressed interest in reintroductions in Texas, US.

The comeback of one of Argentina’s most iconic cats presents an opportunity to enhance the appeal of Iberá as a unique wilderness destination for tourists. By communicating and documenting the arrival, release and adaptation of the ocelots, Rewilding Argentina and Mossy Earth aim to generate more interest among visitors and spread awareness of their role in a functioning, complete ecosystem.

Ocelots released into Iberá

The first two ocelots released into the wild in December 2023 were Tomi and Luna. Below are some images of them exploring their new home and a new arrival named Lila from Paraguay settling into the quarantine facilities in Argentina.

Project Discussion

Project manager, Adriana, gives more background on this project with Rewilding Argentina.

Sources & further reading

- “The ecological role of the mammalian mesocarnivore” - Roemer, Gary & Gompper, Matthew & Van Valkenburgh, Blaire. (2009).

- “Predator interactions, mesopredator release and biodiversity conservation” - Euan G. Ritchie and Christopher N. Johnson