- Management Plan

- Final Report

- Total budget: £5,000

- Budget spent: £3,810

- Status: Implemented

The great crested newt, one of Britain’s flamboyant native amphibians, relies heavily on the health of pond ecosystems for its survival. In an area of Shropshire in the UK, where this protected species is found, we’re working to restore a pond before it disappears completely along with the wildlife that inhabits it. By excavating and enlarging the pond, with our partners Shropshire Wildlife Trust, we hope to secure a breeding ground for the great crested newt, among many other species, for at least the next 30 years.

Project Timeline

Pond Ecosystems

The formation of ponds in Britain

There’s an estimated half a million ponds spread across Great Britain, as such, they are a common characteristic of the landscape. Like much of the land, human influence has shaped how ponds appear today. Historically, many were dug to extract materials for agriculture or used as a water source for livestock, while others were built for wildlife or merely for decorative purposes and some even formed by WW2 bombs. There are also natural ponds called pingos - ancient pools created by trapped frozen water that melted and formed in depressions, some dated at 14,000 years old. Ponds can be both permanent and temporary with seasonal rains affecting the permanence of some ponds.

Oases of Wildlife

We enjoy ponds as an attractive landscape feature but they provide much more than just aesthetic value. Although they are smallish bodies of water (up to 2 hectares in size), they are havens for a wide variety of freshwater species such as amphibians, aquatic plants and large invertebrates. The wonderful array of wildlife that depends on pond ecosystems include frogs, newts, beetles, dragonflies, water fleas, shrimp, and aquatic snails. Water is the source of life for these creatures, where pond ecosystems provide the breeding ground for new life to emerge and buzz with activity.

The perfect pond for wildlife has good water quality, a shallow margin and is wrapped in vegetation to give amphibians and insects shelter during their time on land. Wildlife found in these isolated bodies of water attract other species higher up the food chain to feed on them. Herons, hedgehogs and bats are a few that benefit from the abundance of pond dwelling species. For these reasons, ponds are often called ‘oases of wildlife’ and restoring them is an effective way to boost biodiversity in an area.

Priority Pond Species

The great crested newt (Triturus cristatus) is one of the most high-profile residents of UK ponds. Its grand name comes from the male’s distinctive sawtooth crest that runs along its back during spring breeding season. This, along with their orange/yellow spotted bellies and long flatten tail with a streak of silver makes them a uniquely eye-catching amphibian. Also known as the ‘warty newt’ for its lumpy skin, this slimy species is the largest newt in Europe (females growing up to 7 inches / 17.8 cm).

Great crested newts spend a large part of the year hibernating on land but return to aquatic habitats to breed where they need vegetation to lay their eggs. Females will individually lay and carefully wrap over 200 eggs in the leaves of an aquatic plant, of which half develop into tadpoles. They also need good water quality and the absence of large amounts of fish and wild fowl which eat newt larvae and destroy aquatic vegetation. Due to the degradation of ponds and surrounding terrestrial habitats, the great crested newt is in decline. In the UK and Europe, it is now a protected species under the UK Post-2010 Biodiversity Framework and the European Habitats Directive.

Fun Facts

The life of a great crested newt attracts the attention of naturists for numerous reasons.

- In the wild, they are known to live up to an extraordinary age of 25!

- Armed with a toxin which they secrete from their skin, gives them protection from predators.

- Like all newts, they have the ability to regrow lost limbs.

- In search of mating partners, great crested newts venture up to 1 km. When they find the 'perfect partner' they perform a dazzling courtship dance.

- Great crested newts fulfil their role in the food web enthusiastically as carnivores by devouring a wide range of species like slugs, worms, insects, molluscs and tadpoles.

The Threats to Pond Ecosystems

Pond ecosystems can be negatively affected by various factors that lead to their degradation and disappearance. In many cases, ponds are drained or neglected so they become filled with vegetation and silt (washed into ponds by rainwater) or turn stagnated under fallen leaves. Invasive species can also impact the health of native aquatic plants and dominate the limited space in ponds. Pollution is another cause of degradation with the main source being pollutants from agricultural run-off and urban areas. One estimate puts the loss of ponds over the last century at 50% with 80% of the remaining ponds in poor condition. This greatly affects the chances of freshwater species as 2/3 rely on pond ecosystems.

The pond this project is targeting is in an area known to support great crested newts in Shrewsbury, county Shropshire. The pond is drying out and shrinking to such a state that it will soon no longer be able to sustain the breeding grounds for the newts and other wildlife.

Our Project

This rewilding project aims to restore this pond to provide a large and suitable habitat for the great crested newt that will be available for the next three decades.

To achieve this, we’re working with our partners, Shropshire Wildlife Trust, to excavate and enlarge the pond between October 2022 and February 2023. The plan is to expand the existing pond to 150m² with a depth of at least 1.5m with a shallow sloped shelf to recreate the ideal conditions for wildlife, including establishing microhabitats. This will involve preserving patches of surrounding aquatic plants so they can recolonise. The surrounding area will also be managed to support and improve connectivity to other habitats. To secure long-term success, the landowner is committed to maintaining the wider site in line with Shropshire Wildlife Trust’s advice. This will involve varying levels of management, from a ‘hands-off’ approach to allow for natural growth but also to intervene where necessary to retain an appropriate amount of water, such as monitoring overgrowth of vegetation. However, this isn’t expected to occur for the next 20 years.

Mossy Earth’s members are providing 100% of the £5,000 project budget which includes the cost of excavations, equipment and staff.

Recolonising Newts

We’re hoping the impact of this project will return positive results for biodiversity in the not-too-distant future. Evidence suggests that great crested newts are quick to move in. eDNA testing results say that 42% of ponds are colonised by newts within 2 years after being constructed.

Our partners on-the-ground will be monitoring the effect of this intervention to see if improvements are achieved in the Habitat Suitability Index score. You can learn more about the scientific evidence behind this intervention on the Conservation Evidence database linked in the 'Further Reading' at the end of this page.

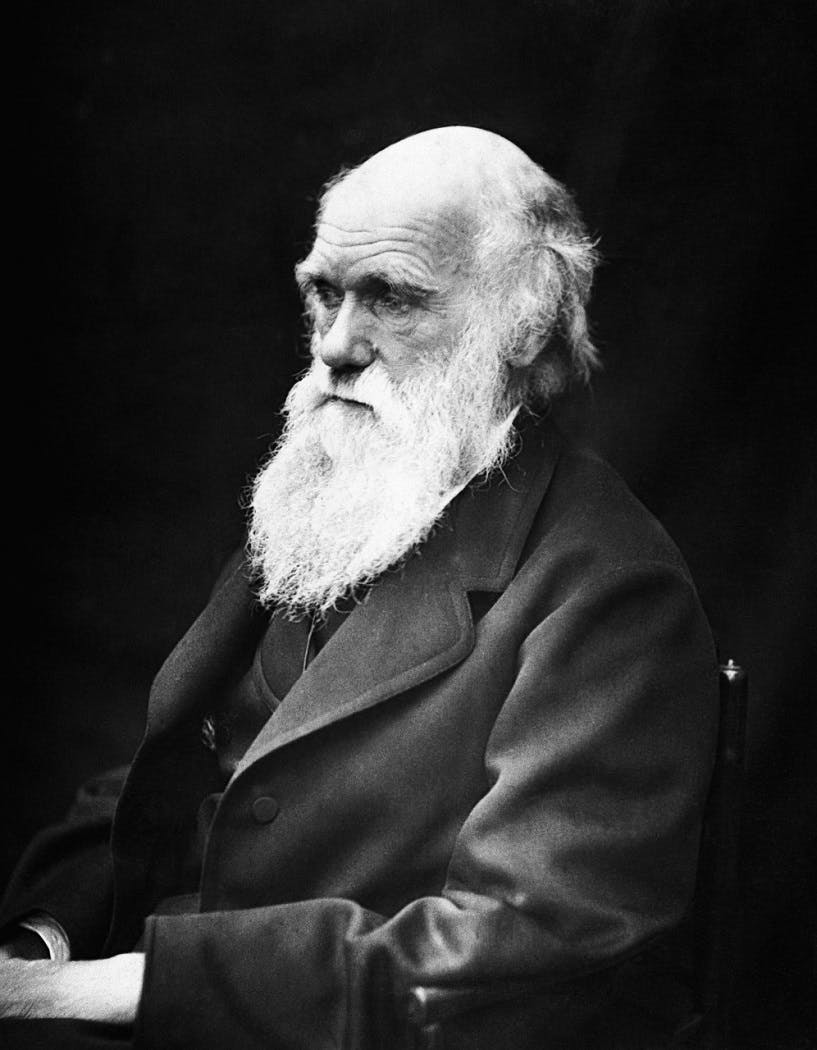

Darwin's Backyard

The beauty of rewilding lets us imagine back to previous states of nature when wildlife was more bountiful. This particular area where this project is happening, could have been one such example. I'll let our project partner; Luke Neal at Shropshire Wildlife Trust explain:

"This pond is next door to Charles Darwin’s childhood home, it's very likely that he would have walked the fields and botanised in the field where we are working."

See this map of how close Charles Darwin's home actually was!

Sources & further reading

- “Deepen, de-silt or re-profile ponds” - Conservation Evidence

- “Ponds and wildlife” - Shropshire Wildlife Trust